Introduction

One of the hardest parts of any data science project is gathering good data. Fortunately, many online data repositories exist for us to use!

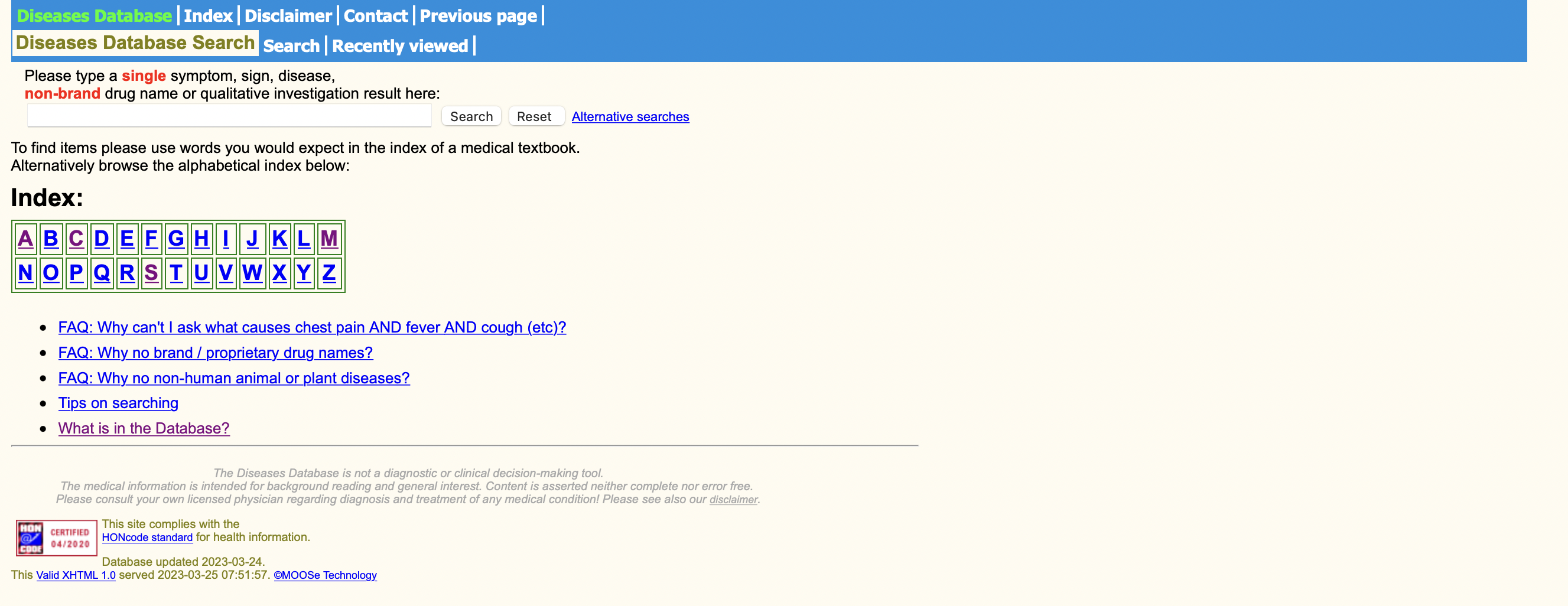

The Diseases Database (DDB) is one such source. The Diseases Database, developed and maintained by Medical Object Oriented Software Enterprises LTD, is a cross-referenced index of human disease, medications, symptoms, signs, and abnormal investigation findings, intended for medical practitioners and students.

Rather than in hierarchies of anatomical, physiological, or pathological systems, it serves as a way of classifying medical concepts along clinical axes, such as cause/effect, risk factors, interactions, etc.

The content focuses on internal medicine, inherited disease, clinical biochemistry, and pharmacology, and is updated regularly, although its last update in the Metathesaurus was in 2001.

For more information, consider checking out the official site of the data. Additionally, the Diseases Database is one of the sources of medical knowledge that contributes to the UMLS, which helps to provide a comprehensive and interoperable knowledge resource for the healthcare domain.

Getting the Data

Unfortunately, DDB does not provide free download of the raw data nor an open API to interact with the data. It even says so on its website.

But that won’t stop us in the name of data science! Web scraping allows us to interact with web pages to extact messy, textual data into clean, organized spreadsheets for our models!

Python has plenty of web scraping libraries to choose from; I personally enjoy working with Selenium because it’s less prone to parsing issues common with Requests package. Additionally, you can interact with it on a live window, and it’s pretty cool to watch!

Web Scraping 101

If you have no idea how to create a custom web scraping file, don’t worry! You only really need access to two peices of information:

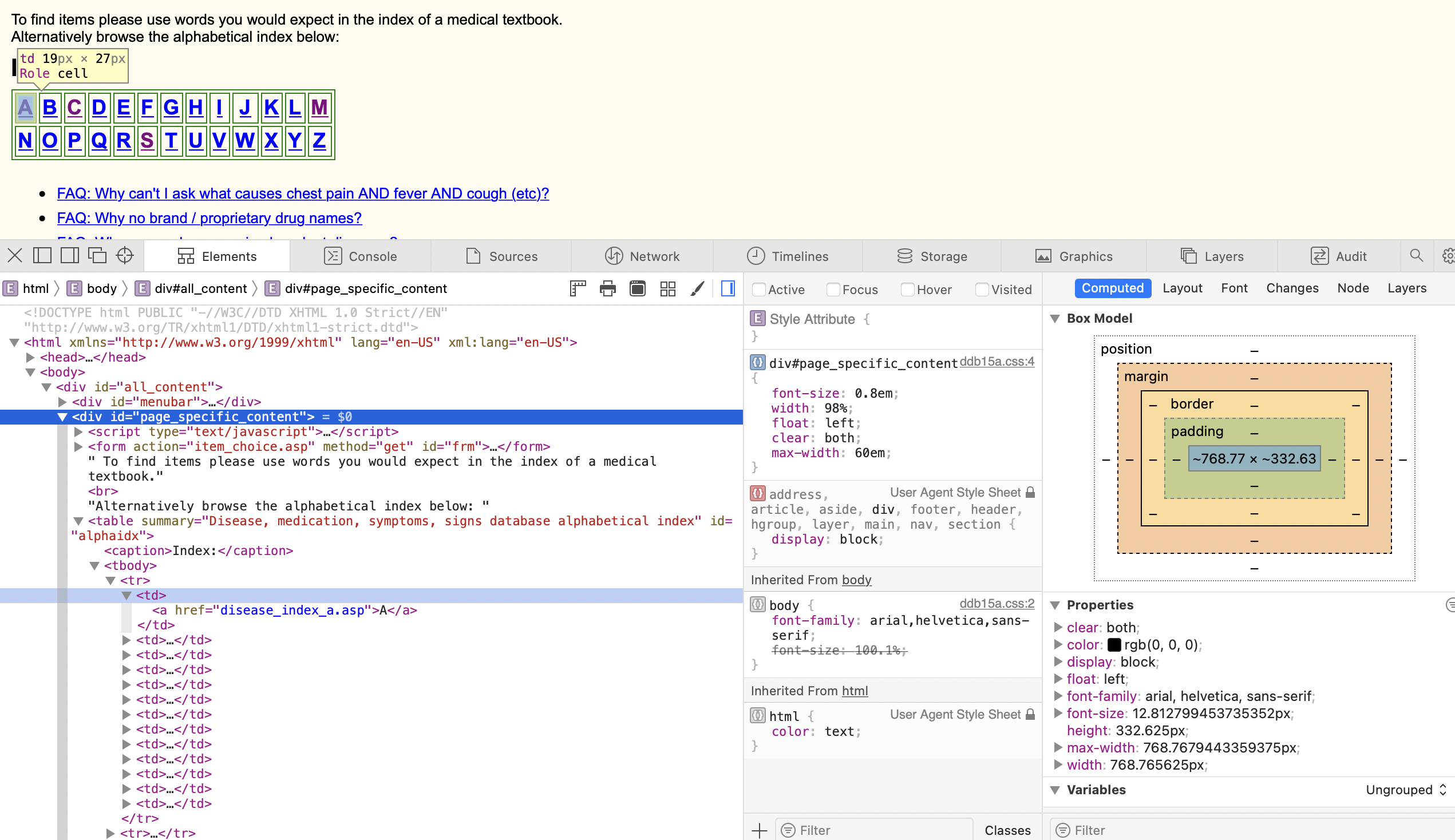

- Access to the web source code (“inspect” element on most web browsers)

- Access to ChatGPT

It’s important to have an idea of how the site appears from a coding standpoint, because this will help guide your prompts for ChatGPT to help.

In the above example, I notice how the home page has a table of all the alphabets, and each letter is a link to a list of all the named medical terms

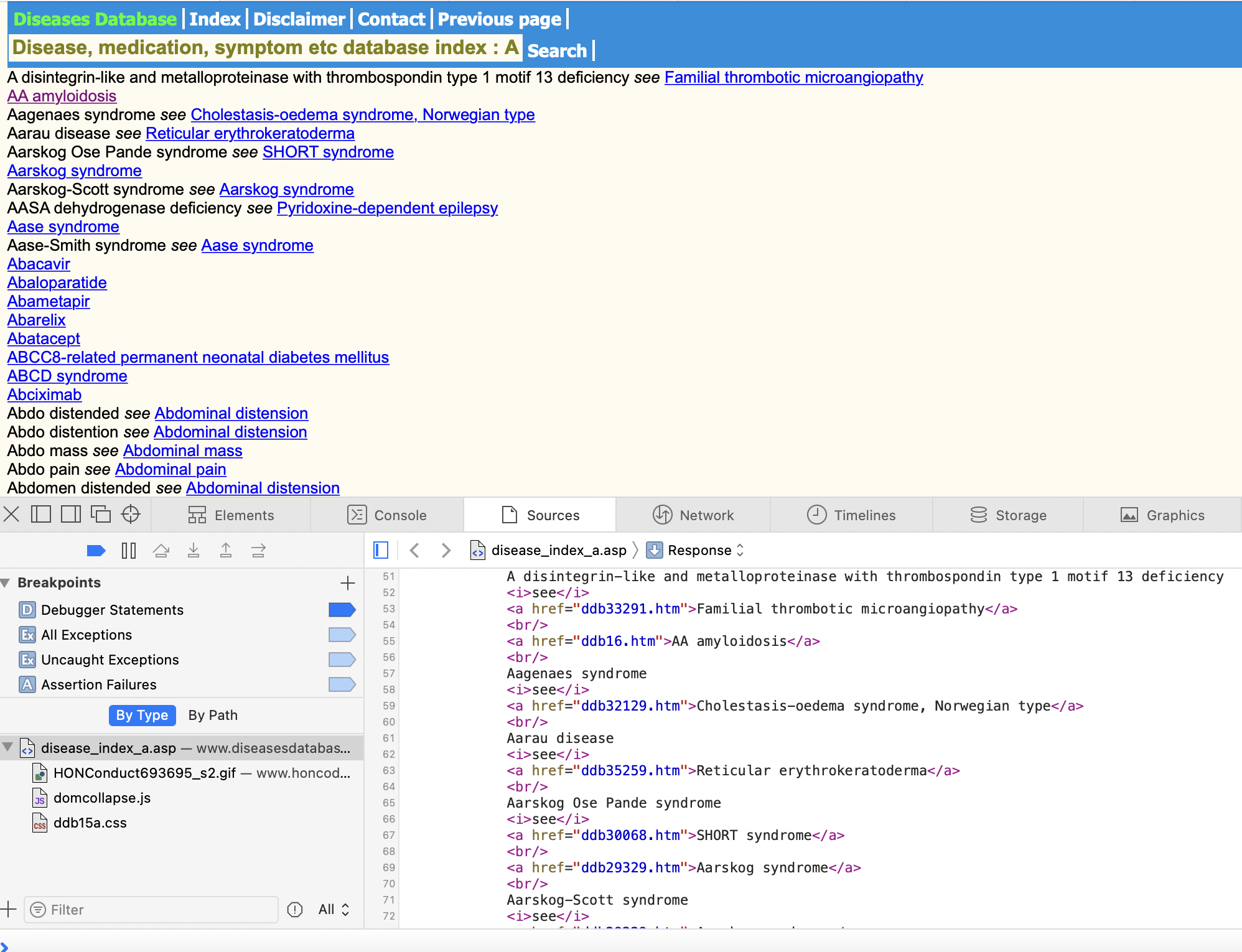

On each listed page, we can also see a common pattern in the web layout: each medical term is a new line, separated by the tag. Moreover, some terms have links, after the word “see”, while others do not (both of these points will be important to know!).

Using ChatGPT

Write a python script that uses selenium==4.8.3 and accomplishes the following items: (1) go to http://www.diseasesdatabase.com (2) sort through the div container with id = “page_specific_content” (3) within the div=“page_specific_content”, loop through and visit all of the a href links inside of the table id=“alphaidx” note there should be 26 links in total (4) within each link, access the div id=‘page_specific_content’ (5) within the div id=‘page_specific_content’, extract all the terms that are separated by the tag using these 2 rules: (rule1) if the fist thing after the tag is not an a tag, but rather text, then extract that text, and move onto the next separated value (rule2) if the first thing after the tag is an a href tag, then extract the words that are within this a tag (in between the opening and closing tags). (6) Save all extracted values into a csv value, where each extracted item is it’s own value.

Now we’re ready to create our prompt for ChatGPT. Above I’ve included by inital prompt to get the web scraping script.

Notice the specific details I use in creating my prompt; I specified using Selenium, the fact that there are multiple links to visit, the name of the div id’s that I’m interested in, how each line is broken, and finally, the fact that I want to save these values into a clean, organized csv file.

Despite this intentional prompt, it took many attempts to fine-tune and adjust my code. This reveals how messy it can be to get a good, fully-functional code from ChatGPT. But as long as you persist, you might end up with something like this:

from selenium import webdriver

import csv

import time

import re

######################################################

################ define regex rules ##################

######################################################

def extract_text_between_br_and_i_tags(html):

# regex pattern to match text between <br> and <i> tags

pattern = r"<br>([^<]*?)<i>|<br>([^<]*?)</a>"

# find all matches in the html

matches = re.findall(pattern, html)

# combine matches and remove blank strings

result = [x.strip() for match in matches for x in match if x.strip()]

return result

def extract_text_between_br_and_a_tags(html):

# Split the HTML by <br> tag

chunks = re.split('<br>', html)

# Initialize an empty list to store the extracted text

extracted_text = []

# Loop through each chunk

for chunk in chunks:

# Check if an <i> tag is within the chunk

if re.search('<i>', chunk):

# If <i> tag is within chunk, then skip and continue

continue

else:

# Otherwise, extract the text that's within the <a> tag

match = re.search('<a[^>]*>(.*?)</a>', chunk)

if match:

extracted_text.append(match.group(1))

return extracted_text

def get_first_entry(html):

pattern = r'<div id="page_specific_content">(.+?)<br>'

match = re.search(pattern, html)

if match:

return "<br>" + match.group(1)

else:

return ""

def extract_first_entry(html):

result = get_first_entry(html)

maybe = extract_text_between_br_and_a_tags(result)

if maybe:

return maybe

else:

return extract_text_between_br_and_i_tags(result)

######################################################

################ run web scraping ####################

######################################################

# Launch the Safari browser

driver = webdriver.Safari()

# Go to the Diseases Database website

driver.get('http://www.diseasesdatabase.com')

# Find the div container with id = "page_specific_content"

page_specific_content_div = driver.find_element('id', 'page_specific_content')

# Find the table with id="alphaidx" within the div container

alphaidx_table = page_specific_content_div.find_element('id', 'alphaidx')

i = 0

# Loop through all the a href links inside the table

with open('output.csv', mode='a', newline='') as csv_file:

# Create a CSV writer object

writer = csv.writer(csv_file)

# Write the header row if the file is empty

if csv_file.tell() == 0:

writer.writerow(['node_name'])

for link in alphaidx_table.find_elements('tag name', 'a'):

# Follow the link

link.click()

# Sleep for 3 seconds

time.sleep(3)

# Find the div id='page_specific_content'

link_page_specific_content_div = driver.find_element('id', 'page_specific_content')

raw_html = link_page_specific_content_div.get_attribute('outerHTML')

lst1 = extract_text_between_br_and_i_tags(raw_html)

lst2 = extract_text_between_br_and_a_tags(raw_html)

lst3 = extract_first_entry(raw_html)

combined_list = lst1 + lst2 + lst3

# Write each element in the combined_list as a new row

for element in combined_list:

writer.writerow([element])

# Go back to the previous page

i += 1

print(f"finished list {i} out of 26")

driver.back()

# Close the browser

driver.quit()

The above code block is divided into two sections: (1) defining the regex rules to parse the raw html code (2) actually running the web scraping tool, applying the regex rules, and saving the results into a csv file. Below is what the function looks like, as it opens a new browser window, loops through the list of links, and saves the output into a csv.

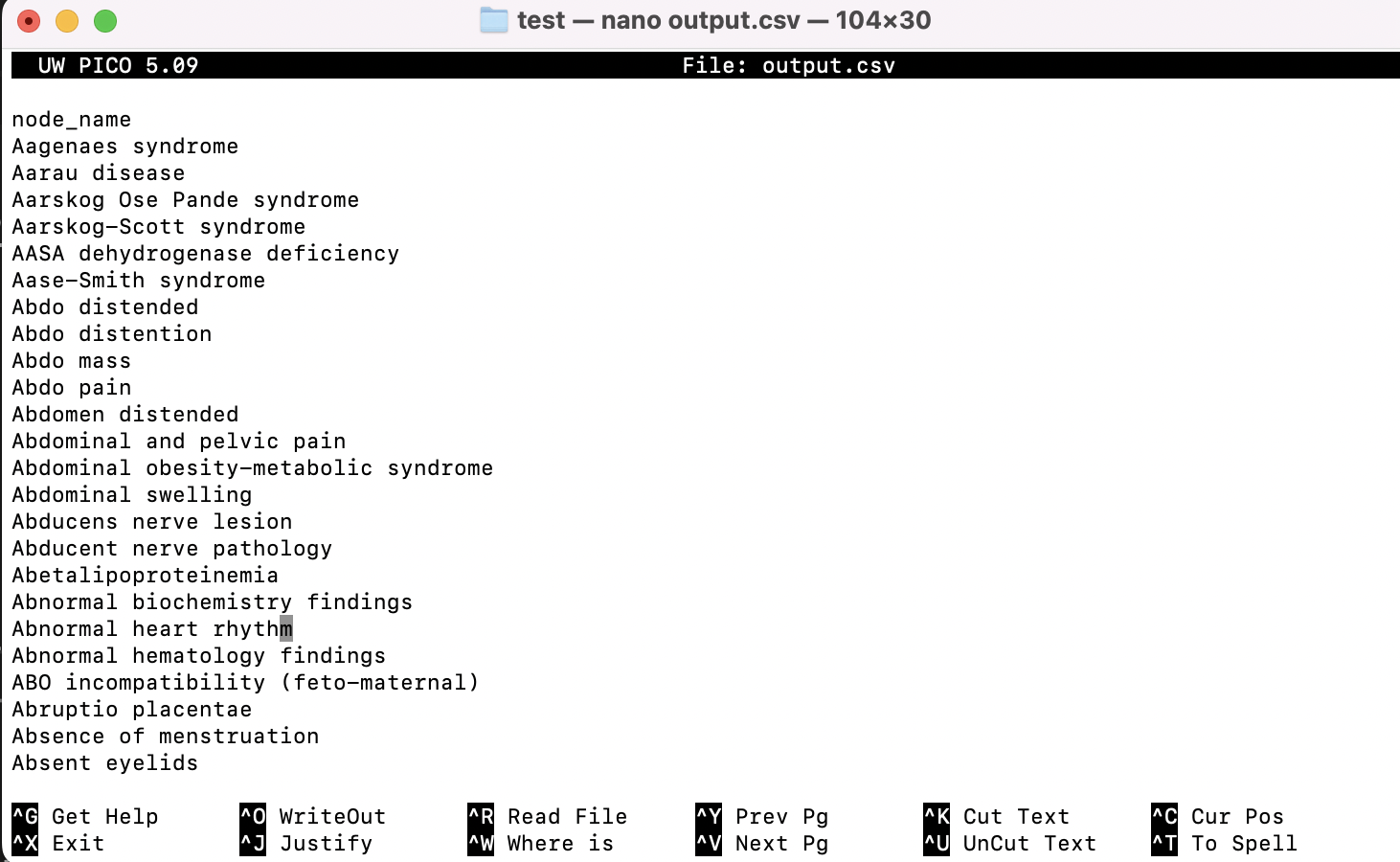

We know we web scraped correctly when we’re left with a file of all the medical terms.

It’s important to note that there is no right or wrong way to web scrape, because each static site is so different, and the way we choose to parse it can vary depending on the tools we use. However, as long as the end result is meant–extracting textual data from the web onto a clean csv file–then all the rest is just details!